Abstract

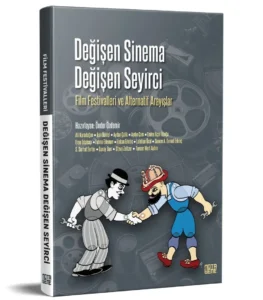

The book Changing Cinema, Shifting Audience: Film Festivals and Alternative Quests (Değişen Sinema, Değişen Seyirci: Film Festivalleri ve Alternatif Arayışları) traces the transformations in cinema and audiences caused by changes in viewing habits and venues resulting from the innovations in cinema technologies since the 2000s. The contributing authors examine film festivals in Turkey and around the world from various perspectives, assessing the possibility of an “alternative” festival outside the hegemonic neoliberal culture industry. The volume’s first section focuses on the changing structure of film festivals in Turkey, precarious labor in festivals and the film industry, censorship mechanisms in festivals, festival audiences, crisis, alternatives, and cultural policies. The second section examines film festivals in other regions and the structure of festivals worldwide, enabling a comparative approach. The remaining sections offer insights from the field, giving space to the voices of festival organizers and directors. This book has been specially prepared for the twentieth anniversary of the International Labor Film Festival (Uluslararası İşçi Filmleri Festivali), which has operated non-competitively, free of charge, and without sponsorship since its inception in 2006. The festival organizers emphasize that cinema is not only an art form but also a tool of solidarity and struggle. In this respect, independent festivals distinguish themselves from festivals that are simply copies of one another and are run with the support of large capital groups. Unlike festivals that receive state support and sponsorship from large corporations, they aim to be an independent and free platform. The studies and interviews included in this work contribute to the visibility of “small” and thematic festivals. This study examines the various layers of film festivals in Turkey and around the world, emphasizing alternative approaches in an effort to understand change.

Keywords: Labor Film Festival, film festivals, cinema, audience, alternative.

Aytaç, O. (2025). Second annual book from the international labor film festival: changing cinema, shifting audience: film festivals and alternatıve quests. sinecine, 16(1), 323-336.

Öz

Değişen Sinema Değişen Seyirci: Film Festivalleri ve Alternatif Arayışlar başlıklı kitap, 2000’lerden itibaren gelişen sinema teknolojilerindeki yeniliklerle beraber değişen sinema salonları ve film izleme alışkanlıklarının sinemada ve seyircide yarattığı değişimin izini sürmektedir. Bu kitaba katkı veren yazarlar Türkiye’deki ve dünyadaki film festivallerini çeşitli boyutlarıyla ele alarak neoliberal hegemonik kültür endüstrisine “alternatif” bir festivalin olasılığını değerlendirmektedir. Türkiye’de film festivallerinin değişen yapısı, festivallerde ve sektörde güvencesiz emek, festivallerdeki sansür mekanizmaları, festival seyircisi, kriz, alternatifler ve kültür politikaları ilk bölümün konuları olarak öne çıkmaktadır. İkinci bölümde ise başka coğrafyalardaki film festivalleri ve dünyadaki festivallerin yapısı ele alınmaktadır. Bu sayede mukayeseli bir yaklaşım geliştirilebilmektedir. Diğer bölümlerde ise sahanın sesine kulak vererek festivalleri düzenleyenlerin ve yönetmenlerin görüşleri yer almaktadır. Bu kitap, 2006 yılında ilk kez düzenlendiği günden itibaren yarışmasız, ücretsiz ve sponsorsuz şekilde hayatına devam eden İşçi Filmleri Festivali’nin yirminci yılı kapsamında özel olarak hazırlanmıştır. Festivali düzenleyenler sinemanın yalnızca bir sanat değil, aynı zamanda bir dayanışma ve mücadele aracı olduğunu vurgulamaktadır. Bu yönüyle bağımsız festivaller, birbirinin kopyası olan ve büyük sermaye gruplarının desteğiyle yürütülen festivallerden ayrışmaktadır. Devletten destek ve büyük şirketlerden sponsorluk alan festivallerin aksine bağımsız ve özgür bir platform olmayı amaçlamaktadır. Bu eserin içerisinde yer alan çalışmalarve söyleşiler, “küçük” ve tematik festivallerin görünürlüğüne katkı sağlamaktadır. Türkiye’deki ve dünyadaki film festivallerini farklı katmanlarıyla inceleyen bu çalışma, değişimi anlama çabasıyla alternatif arayışlara vurgu yapmaktadır.

Anahtar Kelimeler: İşçi filmleri festivali, film festivalleri, sinema, seyirci, inceleme, alternatif.

Değişen Sinema Değişen Seyirci: Film Festivalleri ve Alternatif Arayışlar Hazırlayan: Önder Özdemir, ISBN: 9786052604403, Notabene Yayınları, 2025, 396 s.

Changing Cinema, Changing Audiences: Film Festivals and Alternative Quests

One of the most significant domains of transformation in cinema has been in viewing practices. Increasingly, films are consumed on digital platforms rather than in theaters, with smaller personal screens repla-cing the traditional large cinema screen. Economic considerations –such as ticket prices– alongside control-oriented features, including the abi-lity to pause or stop a film at will, have reinforced this preference for at-home viewing. Film festivals remain among the key events capable of drawing audiences back to theaters, offering distinctive attractions such as off-screen events, post-screening discussions, and the collective expe-rience of watching new and notable films with fellow cinephiles. In this respect, festivals continue to serve as a primary counterforce to the shift away from the cinema hall. Yet even with these advantages, film festivals, recognizing the technological reshaping of cinema and audience practi-ces, are themselves in search of alternatives.

The Workers’ Film Festival, now in its 20th year, had marked its 10th year with the publication of Workers’ Films, Other Cinemas (Başaran, 2015). That volume not only evaluated the festival’s first decade but also articulated the motivations underlying its commitment to showcasing workers’ films. In doing so, it historicized the category of “workers’ films” was through analyses of their global production dynamics and aesthetic forms. The volume, which also includes translated articles, further sou-ght to illuminate the meanings these films acquire within specific social contexts, as well as the conditions and venues in which they are screened.

Similarly, to mark its twentieth year, the Workers’ Film Festival has released a new book project, focusing on film festivals within the broader context of technological innovations and the changing nature of cine-ma and its audiences. Edited by Önder Özdemir (2025), Changing Cine-ma, Shifting Audiences: Film Festivals and Alternative Quests examines film festivals in Turkey and beyond, interrogating the possibility of alterna-tive festival practices within the neoliberal hegemonic cultural industry. The volume addresses a wide range of issues, including the structures of Turkish film festivals, the relationship between censorship and festi-vals, shifting audience profiles, the invisible labor of festival workers, the management of crises and their resolutions, and broader questions of cultural policy.

Changing Cinemas and Festivals

The introductory essay, After 20 Years of Festival Experience, is authored by the editor, Önder Özdemir. This piece recounts the founding story of the Workers’ Film Festival, offering a brief year-by-year overview from its inception to the present, while also highlighting opening nights, films screened, and invited guests. By incorporating visual materials such as festival posters, the essay offers a concise yet valuable contribution to the festival’s institutional memory. Furthermore, by extending greetin-gs to other sponsorship-free festivals –such as the Pink Life QueerFest, Documentarist Istanbul Documentary Days, the Bozcaada International Ecological Documentary Festival (BIFED), and the Which Human Rights? Film Festival– it signals an inspiration to cultivate a network or platform of solidarity.

Elucidating the genesis of this book project following the festival, the essay proceeds to outline its thematic and structural organization. It reviews the content of each section and situates the contributions in relation to one another, noting that the inclusion of interviews with film-makers and cinema workers provides a rare platform for industry voices to be heard. Similarly, the section in which festival organizers respond to questions on various aspects of film festivals and their organization constitutes an important space for festivals to represent themselves.

The first chapter of the volume focuses on the theme of changing cinemas and festivals, covering topics such as cultural policies, the festi-val circuit, representations of worker in cinema, festivalism, audiences, crises, precarious labor, and censorship mechanisms. The opening essay, International Film Festivals, Hollywood, and Cultural Policies: Mainstream Alternatives within the Festival Circuit, by Lalehan Öcal, examines film festivals in the context of Hollywood and cultural policy. It discusses the networks in which both large-scale and “small” film festivals operate, the hierarchical relations between central hubs and peripheral regions, and the tensions generated by gravitational pull, dependence, and resistan-ce to centralization. In her doctoral dissertation, Öcal (2013) investiga-ted the relationship between film festivals and narrative, revealing how films labeled as “independent” often remain reliant on festival funding – dependencies that, in turn, shape narratives in ways that construct a Eurocentric ideological discourse. Following her analysis of networks shaped by Orientalism and colonialism, Öcal locates hope in “small” fes-tivals, proposing them as alternatives to what she terms the dominant zero-gravity world cinema regime (2021).

The study underscores how the West approaches non-Western contexts from a colonial legacy perspective, and how funding mechanis-ms enable it to remain exempt from the social and political crises repre-sented in films from the Global South. It further argues that the institu-tional discourse within parallel festival universes can be overcome only through collective struggle, citing the Bozcaada International Festival of Ecological Documentary (BIFED) as an example. By addressing environ-mental concerns beyond the narrow confines of “environmental films” and facilitating diverse encounters, BIFED challenges the commodifica-tion of ecological discourse. The categorization system of the Internati-onal Federation of Film Producers Associations (FIAPF) is critiqued as a form of capitalist institutionalization, with Öcal warning that festivals founded on alternative ambitions may themselves drift into mainstream tendencies. The concept of the “festival circuit” is examined as a network composed of multiple dynamics, actors, and relationships – an arena that is inherently competitive yet also capable of fostering collaboration among thematic festivals. Such potential for thematic alignment serves as a source of optimism for small-scale thematic film festivals.

Framing Hollywood as the “fortress of cultural policy” (Miller, 2021), the article traces the historical trajectory of the Academy Awards while questioning whether, in recent years, Hollywood has positioned it-self as a stakeholder in the mainstream festival circuit by acknowledging films that had already received major festival prizes. In this context, Pa-rasite (Bong Joon-ho, 2019), Nomadland (Chloé Zhao, 2020), The Substance (Coralie Fargeat, 2024), and Emilia Perez (Jacques Audiard, 2024) are anal-yzed through the lens of misleading representational mechanisms and political strategies that obscure class consciousness.

The second essay in the Changing Cinemas and Festivals section, The Working-Class Subject, Festivalism, and Alternative Quests in New Inde-pendent Turkish Cinema: The Workers’ Film Festival, stands out as the only chapter in the volume devoted specifically to Turkish cinema. Authored by Aslı Daldal, it builds on her earlier article, The Disappearance of the Working-Class Subject in the New Independent Turkish Cinema of the 1990s: Globalization and Festivalism (2021), by incorporating a new section on the Workers’ Film Festival. The piece examines the disappearance of the working-class subject in post-1990 New Independent Turkish Cinema, situating the discussion within the frameworks of globalization and fes-tivalism. It argues that so-called auteur cinema in Turkey after 1995 adop-ted an increasingly individualistic orientation, avoiding political issues in favor of themes such as identity crises. This argument is supported by examples drawn from the early works of directors such as Nuri Bilge Ceylan, Zeki Demirkubuz, Reha Erdem, and Yeşim Ustaoğlu.

Highlighting the rise of neoliberal policies worldwide after the 1980s and the attendant processes of globalization, the essay situates the economic and political shifts of this period within the broader cultural field, with particular attention to cinema. It underscores the relations-hip of dependency between New Independent Turkish Cinema and film festivals, drawing parallels to similar patterns in other art forms that result in repetitive creative output – a phenomenon described as festi-valism. The essay, which captures the problematic state of New Indepen-dent Turkish Cinema within the framework of festivalism, turns to the Workers’ Film Festival in terms of the potential of festivals to serve as counter-hegemonic public spheres (Killick, 2015).

The festival’s founding narrative is recounted alongside its guiding principles –most notably, its commitment to operating without adver-tisements, competitions, or sponsorship– underscoring its class-based orientation. Distinguishing itself from human-rights-themed festivals through its explicit focus on class, the Workers’ Film Festival’s differen-ce is illustrated by examples from events and selections at the Istanbul and Ayvalık Film Festivals. Its annual thematic focus is presented as an expression of its view of cinema as a site of struggle, while its itinerant format –bringing the festival to multiple cities– is noted as one of its key strengths. Alongside BIFED and Documentarist, the Workers’ Film Festival is positioned as one of the most promising initiatives offering an alternative to the neoliberal cultural industry’s incorporation of globali-zation and festivalism.

Another contribution in the first chapter, Film Festivals and Their Audiences, derives from the TÜBİTAK 1001 research project no. 121K324, The Structure, Economy, Operation, and Audience Profile of Film Festivals in Turkey. Authored by Hakan Erkılıç, Senem Duruel Erkılıç, Aydın Çam, Ali Karadoğan, Emine Uçar İlbuğa, and Serhat Serter (the project’s director and researchers), the article classifies four major Turkish film festivals – Istanbul Film Festival, Antalya Golden Orange Film Festival, Ankara Film Festival, and Adana Golden Boll Film Festival– as “audience festivals.”

Drawing on survey and interview data collected as part of the re-search, the article presents demographic and behavioral profiles of fes-tival audiences, including age, gender, education level, occupation, and patterns of festival attendance. It analyzes audience motivations across categories such as women, students, and individuals over the age of 55, offering distinct interpretations for each group. Audience perspectives on programming strategies, along with their critiques of the festivals, are also discussed. The findings are visually represented through tables and graphs, facilitating concise comparisons with previous studies on the subject. In doing so, the article examines changes in audience pro-files over time, also exploring how festivalgoers perceive the concepts of cinephilia and cinema enthusiasm. The heightened interest in cinemas during festival periods is interpreted as a form of event-based cultural participation. Referring to the concept of “audience festivals” (Peranson, 2009) and the specific identity of festival audiences, the study concludes by suggesting strategies to strengthen this relationship.

The next piece, The Crisis of Cinemas and Alternative Quests, autho-red by the volume’s editor Önder Özdemir, takes as its point of departure a question posed by Wim Wenders in his 1982 documentary Room 666, filmed during the Cannes Film Festival: “Is cinema a language about to be lost, an art about to die?” Building on this question, Özdemir exami-nes the transformation of movie theaters in the era of digitalization. He observes that the division and multiplication of cinema halls signaled the decline of open-air and neighborhood theaters. In 2005, the Digital Cine-ma Package (DCP) format was introduced as the standardized mode of exhibition, and cinema owners were encouraged to adopt it thus promp-ting a technological overhaul of projection infrastructure. The COVID-19 pandemic, coupled with the concurrent surge in streaming platform subscriptions, further deepened the crisis confronting cinemas and reig-nited debates concerning the future of the medium.

The article discusses alternative practices to overcome this crisis, highlighting the FilmKoop initiative as a key example. Related activities include the Cinema at the Cinema Festival, Sinematek screenings, and events organized by the Lüleburgaz and Datça Cinema Communities. One notable outcome of these efforts was the introduction of KOOPlay, a screening device produced as an alternative to DCP. This device, equip-ped with the ability to track the number of screenings, enabled collabo-rations with several municipalities under the City Cinema project. Advo-cating the possibility of a new and alternative cinema culture, the article grounds its claim in the concrete practices it documents and maintains optimism about the potential for their broader dissemination.

Another essay in the first chapter, Changing Festivals, Precarious Labor, and the Role of the Workers’ Film Festival, by Emine Uçar İlbuğa, fo-cuses on the increasingly precarious labor conditions within the film fes-tival sector. The project-based nature of work and the resulting depen-dencies foster an environment in which job security is absent. The article argues that, due to insufficient institutionalization, the sector remains far from achieving the stability of a fully developed industry – a conditi-on that equally affects festival workers.

Through a comparative analysis of the Istanbul Film Festival, An-kara Film Festival, Adana Golden Boll Film Festival, and Antalya Golden Orange Film Festival, the article also addresses instances of censorship within these festivals. Despite the adverse conditions affecting both the sector and festivals, the Workers’ Film Festival is presented as an example of collective solidarity. The article emphasizes the importance of festivals serving as arenas for such struggles, advocating for organi-zed movements rooted in labor rights as a way to overcome the sector’s structural problems.

The final article of the first chapter, Censorship Mechanisms and Ac-tors in Film Festivals in Turkey after 2000, by Sonay Ban, revisits her ear-lier two-part article Cinema Censorship in Turkey after 2000 (published in Altyazı Fasikül), reframing it through the lens of film festivals. The study outlines the history of censorship in Turkish cinema and examines how festival structures shape censorship practices. Festivals are classified into three categories: those sponsored by banks or foundations, those supported by municipalities or governorships, and small-scale indepen-dent festivals.

By compiling and cataloguing cases of censorship at festivals, the article seeks to counteract the widespread lack of collective memory on the issue and to reposition censorship as a contemporary phenomenon rather than a relic of the past. Through specific examples, the study il-lustrates the breadth and diversity of censorship incidents, noting that, unlike in earlier decades when the state intervened directly, censorship at festivals today is often exercised indirectly through state-appointed intermediaries. Justifications vary from the absence of an exhibition li-cense to vague appeals to “public peace”, but the persistence of censors-hip remains evident. The article also highlights the case of Kanun Hükmü (2023) and addresses the dynamics of self-censorship, concluding that as long as films can be deemed “objectionable,” festivals will continue to be shaped by the broader atmosphere of censorship.

Alternative Film Festivals at the Other Geographies

The second section of the book consist of four studies, the first of which is authored Eren Odabaşı and titled Non-Profit Cultural and Artistic Ins-titutions and International Film Festivals. This study compares two dis-tinct organizational models: cultural and artistic institutions that host year-round screenings and film festivals. Highlighting the differences between North American cultural institutions and European film festi-vals, the article notes that while sponsorship and external funding are prevalent in film festivals, year-round events organized by cultural ins-titutions tend to depend more heavily on volunteer labor and donations.

Odabaşı underscores the role of volunteer labor in shaping the institutional identity of film festivals. He suggests that the differences between North American and European models are difficult to apply di-rectly to festivals in Turkey. However, he argues that, due to its lack of sponsorship and reliance on volunteer labor, the Workers’ Film Festival more closely resembles North American cultural institutions more than the European festival model. The author also discusses documentary, short film, and women’s film festivals in Turkey, offering broader obser-vations on thematic festivals within this context.

Two case studies are examined in detail: SIFF Film Center and Pickford Film Center. Both are non-profit cultural institutions that, in addition to organizing screenings and events throughout the year, also host the Seattle International Film Festival and Doctober, respectively. Sustained by volunteer labor and financial contributions, these instituti-ons have successfully staged impactful festivals within their regions, ma-king them ideal examples for exploring the relationship between cultural institutions and film festivals. Drawing on interviews with institutional representatives, the study provides data on audience profiles, financial structures, activities, collaborations, and staffing. While the replication of such strategies may not be feasible in every national context, the study provides an optimistic exploration of models for organizing events wit-hout reliance on sponsors or external funding.

The second article in the same section, The Construction of Natio-nal Identity through Festivals: Turkish Film Festivals and Other Festivals, by Tuncer Mert Aydın, revises his earlier work, The Structure of Transnatio-nal Turkish Film Festivals in Germany and the United States during the CO-VID-19 Pandemic, which was originally presented at the First Symposium on Film Festivals and later published in Film Festivals Book 1. Adopting a historical perspective, the article examines the capacity of film festivals to construct national identity, while also addressing their broader fun-ctions. It situates the Workers’ Film Festival as an example of a festival that foregrounds class identity, rather than national identity, through its emphasis on the working class. The discussion draws on examples from Turkish Film Days events in the United States and Europe, highlighting how diaspora and migrant identities are expressed through cultural ac-tivities. Insights into these events are further enriched by interviews with the directors of the Hollywood Turkish Film & Drama Days and the Munich Turkish Film Days. The study concludes that such festivals not only contribute to the construction of national identity but also serve as platforms for fostering transnational cultural diplomacy.

The third article, Reconstructing Identity in the Diaspora: Kurdish Film Festivals, is authored by Fatma Edemen, whose doctoral dissertation in Poland forms the basis of this work. The study examines the emergen-ce of Kurdish film festivals in Europe, framing them as solidarity platfor-ms that go beyond mere screening events. Drawing on Pierre Bourdieu’s field theory, the article conceptualizes these festivals as cultural arenas in which struggles over legitimacy take place. It argues that Kurdish film festivals serve as critical tools for overcoming issues of cultural legitima-cy and for enhancing the visibility of Kurdish cinema. The individual suc-cesses of Kurdish directors such as Yılmaz Güney and Bahman Ghobadi in European film festivals are understood to have been transformed into a collective platform through the establishment of Kurdish film festivals. The sustainability of these festivals is thus presented as essential for ma-intaining their visibility on the international stage.

The final two contributions in this section are by Steve Zeltzer. The first, The Workers’ Film Festival on a Growing Curve and Network, originally published in the Workers’ Film Festival newspaper in 2008, summarizes the trajectory of the festival since its early years. It highlights connecti-ons between protests and screenings spanning from Japan to Denmark, emphasizing the role of labor film festivals in making class struggles vi-sible. The article also discusses plans for the creation of an international labor media network designed to encompass not only films but also pho-tography, video, and music.

Zeltzer’s second article, The LaborFest Experience in the United Sta-tes, describes how LaborFest, first organized in the U.S. in 1994, has ex-panded to other parts of the world. It demonstrates how the festival mo-bilizes images and documents to contribute to ongoing struggles, while also addressing broader social issues such as racism and xenophobia alongside labor struggles. The article further notes that technological advancements have enabled workers to use social media more effectively in activism and suggests that such productions can be integrated into festivals alongside films.

Directors, Cinema Workers, Films, and Festivals

The third chapter of the book is devoted to directors and cinema workers. It compiles interviews conducted by festival volunteers for the Workers’ Film Festival newspaper in 2008, 2009, 2011, 2013, 2014, and 2016. Under the title Directors Talk about Workers’ Cinema, conversations are presen-ted with Erden Kıral, Şerif Gören, Tayfun Pirselimoğlu, Yeşim Ustaoğlu, Özcan Alper, Ezel Akay, Zeki Demirkubuz, Ümit Ünal, Derviş Zaim, Kazım Öz, İnan Temelkuran, İlksen Başarır, Seyfi Teoman, and Hüseyin Karabey.

In addition to this set, the chapter features interviews feature with a wide range of figures, including Türkan Şoray, Ahmet Soner, Ömer Uğur, Soner Sert, Özcan Alper, Hikmet Dikmen (a cinema worker from Emek Movie Theater), İlksen Başarır, Seren Yüce, Sedat Yılmaz, Reyan Tuvi, Eylem Şen, Metin Kaya, Majid Majidi, Bahman Ghobadi, Miche-langelo Severgnini, Tokachi Tsuchiya, Ken Loach, and Kenan Önalan, a volunteer from the Barrier-Free Access Group. The diversity of interviewees extends beyond directors to include actors, writers, and other film professionals. Special attention is given to representing a range of perspectives, encompassing documentary filmmakers, disability perspe-ctives, labor issues, and international representation.

Independent Festivals Speak for Themselves

The final chapter allows independent film festivals to articulate their own perspectives. Contributions are included from the Bozcaada Inter-national Ecological Documentary Festival (BIFED), Documentarist Istan-bul Documentary Days, Which Human Rights? Film Festival, Pink Life QueerFest, and the International Workers’ Film Festival. These festivals, which focus on themes such as environment, human rights, LGBTQ+, and class, respond to a set of twelve questions.

Within this framework, the responses address a wide range of the topics: from whether screenings are free of charge to the payment of copyright, the presence or absence of sponsorship, the types of films shown; to the distinctive features of each festival, the organization of competitions, the cities in which the festival is organized, its longevity, the composition of the organizing teams, the process of film selection, the festival’s self-definition, and its origins.

Through these responses, readers gain insight into the identity, aims, organizational and financial structures, host cities, histories, de-mocratic processes, and ethical approaches of these festivals. The inter-views offer valuable perspectives on thematic and independent festivals in Turkey, appealing not only to professionals working in the field, but also to cinephiles interested in festival culture. For those considering es-tablishing a festival, these experiences may serve as both guidance and inspiration. While edited academic collections often privilege scholarly essays over on-the-ground experiences, this book successfully balances theoretical analysis with field-based narratives, creating a synthesis that invites a diverse readership from within and beyond academia.

The Festive Spirit of Cinema: Film Festivals

Film festivals can be understood as cinema’s “festive atmosphere,” uniting off-screen events, city-wide cinematic excitement, newly relea-sed films, and visiting guests. Despite technological changes that have at times challenged and at other times advanced cinema, film festivals have consistently preserved their distinctive place within the cinematic landscape. Even when audiences have drifted away from theaters due to economic or sociological factors, cinephiles have continued to engage with festivals, sustaining a close and enduring bond between audience and festival.

This unique relationship has led to the emergence of “festival stu-dies” as a distinct field within international academic literature. In Tur-key, this area has only recently begun to develop, with initiatives such as the TÜBİTAK project The Structure, Economy, Operation, and Audien-ce Profile of Film Festivals in Turkey, symposia dedicated to film festivals, and their resulting publications paving the way forward. Four symposia focusing on different themes, along with the publication of the papers presented, have played a significant role in expanding Turkish-language scholarship on the subject. The inclusion of findings from the TÜBİTAK project in Changing Cinema, Shifting Audience: Film Festivals and Alterna-tive Quests –a volume marking the 20th anniversary of the Workers’ Film Festival– further strengthens the book’s position within this growing field.

Building on the Film Festivals Book series (Volumes 1–3), this spe-cial volume offers a multifaceted examination of festivals both in Turkey and abroad. While some chapters are revised versions of earlier works, their compilation in a dialogic format addresses an important gap in the existing literature. The book’s originality lies not only in its international scope, which extends beyond Turkish festivals, but also in its inclusion of contributions from festival organizers, providing direct insights and testimonies from the field.

Given Turkey’s challenging economic and sociological conditions, sustaining film festivals as cultural focal points will remain essential for generating both scholarly knowledge and practical resources in the field. This volume serves as a complement to the festival’s earlier 10th-anni-versary book, which focused on workers’ films, and it is hoped that future publications will not require another decade-long wait.

References

- Ban, S. (2023). Devletin Vekilleri: 2000 Sonrası Türkiye’de Sinema Sansürü. Altyazı Fasikül https://fasikul.altyazi.net/seyir-defteri/devletin-vekilleri-2000-sonrasi-turkiyede-sinema-sansuru-bolum-1/ Accessed: 14.08.2025

- Başaran, F. (Ed.) (2015). İşçi Filmleri, Öteki “Sinemalar”. Yordam.

- Daldal, A. (2021). 1990’ların Yeni Bağımsız Türk Sineması’nda Emekçi Öznenin Kayboluşu: Küreselleşme ve Festivalizm. Kültür ve İletişim, 24 (1)(47), 159-189.

- Killick, A. (2015). Film Festivalleri ve Karşı Hegemonya (H. Yüksel, Trans.). In F. Başaran (ed.) İşçi Filmleri, “Öteki” Sinemalar. pp. 309. Yordam Kitap.

- Miller, T. (2021). Hollywood, Kültür Politikası Kalesi, Sinemayı Anlamak (E. Yılmaz, Trans.). In M. Wayne (ed.) Marksist Perspektifler. pp. 171-182. De Ki.

- Öcal, L. (2021). Yerçekimsiz Dünya Sineması. Notabene.

- Özdemir, Ö. (2025). (Ed.). Değişen Sinema Değişen Seyirci: Film Festivalleri ve Alternatif Arayışlar. Notabene.

- Peranson, M. (2009). First you get the power, then you get the money: Two models of film festivals. Cinéaste, 33(3), 37-43.

Kaynak: Sinecine